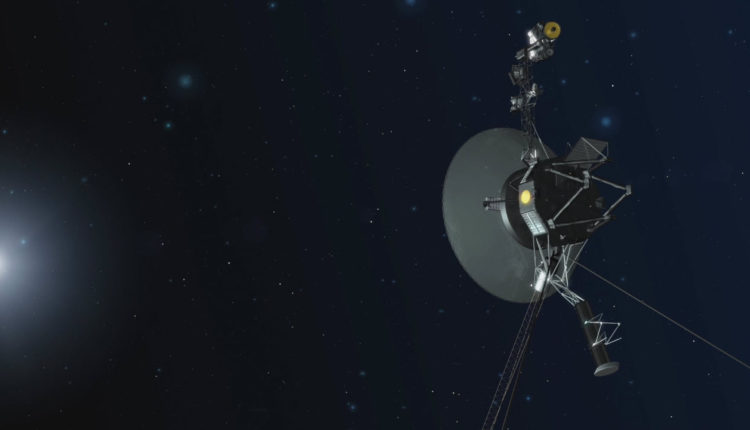

NASA’s Voyager 1 Space Probe Detects ‘Persistent Hum’ 14 Billion Miles Away From Earth

The Voyager 1 spacecraft flew by Jupiter in 1979, and the next year by Saturn, before crossing the heliopause — the solar system's border with interstellar space — in August 2012. It has now reached the interstellar medium.

NASA’s Voyager 1 probe has picked up an uncanny humming sound coming from space. NASA launched the Voyager 1 space probe 44 years ago and today it is the most distant human-made object from Earth, after exiting our solar system nine years ago.

Since then, it has been exploring the near-emptiness of interstellar space and sending back valuable data to help us understand the world outside our solar system. Scientists now say instruments aboard the distant spacecraft have detected a “persistent hum” generated by the constant vibration of small amounts of gas in interstellar space.

According to research published in the journal Nature Astronomy, this persistent monotonous humming is the sound of plasma waves oscillating and it is very weak.

A Cornell University-led team is studying the data sent by Voyager 1 from 14 billion miles away. Stella Koch Ocker, a doctoral student at Cornell University in New York, and one of the authors of the research, said the sound was very faint and monotone because it is in a narrow frequency bandwidth. You can listen to the sound here.

The Voyager 1 spacecraft flew by Jupiter in 1979, and the next year by Saturn, before crossing the heliopause — the solar system’s border with interstellar space — in August 2012. It has now reached the interstellar medium.

Previously, too, after crossing the heliopause, Voyager 1’s Plasma Wave System detected oscillations in the gas, but those were caused by our Sun.

“The interstellar medium is like a quiet or gentle rain,” said senior author of the study James Cordes in a statement on Cornell University’s website.

Researchers now believe that there is more activity going on in the interstellar gas than previously thought. Voyager-1’s data can help scientists understand the interactions between the interstellar medium and the sun’s solar wind, a steady stream of charged particles.

Cornell research scientist Shami Chatterjee explained why continuous tracking of the interstellar space is important, saying scientists never had an opportunity to evaluate interstellar plasma but they do now as the Voyager 1 is flying through them and sending back data.